A recent Bloomberg article by climate economist Gernot Wagner carries the provocative title: “Why Oil Giants Figured Out Carbon Costs First.” Wagner claims that back in the early 1990s, Exxon had internal estimates of the proper “price” to put on carbon that were much better than those of leading academics. Yet Wagner’s article showcases how utterly misleading the pro-carbon tax crowd can be when “educating” the public.

The 1991 Exxon calculation wasn’t at all what Wagner claims, and so the entire premise of his article collapses. What’s worse, when Wagner discusses the current state of the knowledge, he passingly refers to the actual consensus estimates, but then somehow manages to convey the impression that everybody in the field knows the true number is ten times higher. The whole article is yet another example of my long-standing claim that calculating “the social cost of carbon” is a farce: The peer-reviewed literature generates estimates, and then proponents of aggressive intervention throw these figures out the window and list all the reasons that the “real” number is much higher.

Did Exxon “Know the Truth” Back in 1991?

Wagner first defines the concept of the social cost of carbon (SCC): it is the (present-discounted) dollar value of the future flow of net external damages to humanity from the emission of an additional unit of carbon dioxide. Because these are external damages—meaning they accrue to third parties who aren’t deciding to emit the CO2—the normal market price system allegedly fails to incorporate their harm, leading people to emit too much. This is the textbook argument for a carbon tax or other government interventions in the energy and transportation sectors.

Wagner admits that William Nordhaus—who won the Nobel Prize for his pioneering efforts back in 2018—started the enterprise of estimating the SCC in 1992 with a very low estimate of about $2.50 per ton (in today’s dollars). But because of changes in his model and the inputs given by climate scientists, Nordhaus has refined his estimates over the years and more recently calculated the SCC to be closer to $40 per ton. As Wagner also explains, this type of analysis is what guided the Obama Administration in its own interagency working group’s estimates for the SCC.

The Climate Leadership Council (CLC) also picked $40/ton as the starting point for its signature carbon tax. Exxon publicly endorses the CLC plan. Now here’s where things get interesting, as Wagner informs us:

Has Exxon seen the light? Is $40 the magic number?…

Not so fast.

For one thing, Exxon itself knew better a year before Nordhaus first published DICE. In April 1991, Imperial Oil, based in Calgary, Alberta, and controlled by ExxonMobil, issued an internal “Discussion Paper on Global Warming Response Option” with a preface signed by its then-chairman and -chief executive officer, estimating the need for a price of around $75 per ton of CO₂ (in today’s U.S. dollars) to stabilize Canada’s carbon emissions. That is 30 times more than what Nordhaus proposed as the “optimal” price a year later.

…

To be clear, the Exxon report was a very different document from Nordhaus’s DICE model. For one thing, it didn’t calculate the SCC. Exxon’s $75 was simply the number calculated to stabilize Canada’s CO₂ emissions. That’s far from a trajectory that balances global benefits of emissions reductions with its costs. [Bold added.]

Although he introduces it with the phrase “To be clear,” the part I’ve put in bold in the quotation above actually destroys the entire premise of Wagner’s article. The people working (indirectly) for Exxon had apparently performed a calculation to determine that a $75/ton tax on carbon dioxide would be necessary in order to stabilize Canadian emissions. But whoever said that this calculation was the same thing as calculating the socially optimal “price” on carbon? As Wagner admits, that’s not the exercise they were performing.

Look, by the same token, bean counters at Disney World could estimate the price they would need to charge for admission in order to stabilize the number of annual visitors to the Magic Kingdom. But such a calculation wouldn’t make it the right price.

Wagner is simply taking it for granted that the correct thing for humanity to do back in the early 1990s would be to stabilize Canadian (and presumably, global) emissions much more rapidly than in fact happened. Yet that’s the very issue under dispute. Nordhaus’ model—which to repeat, was one (of three) selected by the Obama Administration when trying to quantify the harms of climate change—actually says that the “economically optimal” carbon tax would allow for a cumulative 3.5 degrees (!) Celsius of warming by the year 2100.

For all we know, if someone had informed him back in 1992 of the Exxon calculation, Nordhaus would have responded, “Yes, I agree that a tax on carbon around $75/ton would be necessary to stabilize Canadian emissions, but so what? That would be far too aggressive a brake.” So it’s not at all clear that the Exxon people running those calculations in 1991 were looking at things differently from the expert of the day (i.e. Nordhaus).

The Literature Supports Nordhaus, Not Wagner

Now it’s true, Wagner argues that Nordhaus’ estimates are woefully inadequate. He is free to do so, of course, and maybe he’s right. But Nordhaus just won a Nobel for his work, whereas Wagner is a Clinical Associate Professor at NYU. (To be sure, Wagner has a much more prestigious academic post at the moment than I do—I’m just explaining the “on paper” credentials of Nordhaus versus his critic.) And this brings us to the second piece of misdirection in Wagner’s article, where he somehow tries to convince the reader that Nordhaus’ Nobel-winning work is now understood by all the experts to be wrong:

The economics profession has made important headway on how to calculate climate damages, but there’s still a long way to go.

Almost every time someone tinkers with [Nordhaus’] DICE [model] to change one or two key inputs, SCC figures go up. If you include the fact that climate damages hit growth rates, not levels of gross domestic product, prices increase from $40 to $200 or more. If you look to a different model and assess country-level damages, the average might surpass $400 per ton. Now go to a different model altogether and look to financial economics for insights on how to deal with climate risk; my co-authors, Kent Daniel and Bob Litterman, and I were unable to get the price below $100. [Bold added.]

The parts I’ve put in bold are why I’m claiming that Wagner is trying to convince his readers that we shouldn’t really trust Nordhaus’ estimate. Gosh, once you start really thinking about the complexities of climate change—not like that slouch Nordhaus—you end up with SCC estimates that are double or even ten times his own estimates. Try to keep up, old man!

And yet, the other peer-reviewed estimates of the SCC are in line with Nordhaus’ approach. For example, Richard Tol—who developed another of the three models used by the Obama Administration in its own calculations—has been periodically updating his reports on all of the published estimates; here is his 2018 journal article. If you select a 3 percent “pure rate of time preference” (more on this choice below), then Tol (2018) reports that the literature indicates a mode SCC estimate of $28/ton and a mean SCC estimate of $44/ton.

And even more recent than his 2018 article, on February 15 of this year Tol tweeted out the fact that “[t]he number of estimates of the social cost of carbon has tripled since 2013” but yet “[t]he average estimate has not changed.”[1]

Lots of Moving Parts When Reporting “the” Social Cost of Carbon

I should caution the reader that it’s very difficult to consult the published economics literature and come up with “the” estimate of the social cost of carbon (for a given year), because there are several moving parts. Even if two economists stipulate the same basic climate model, their differences on the appropriate tradeoff between present and future damages (for example) might lead to an enormous difference in the implied estimates of the SCC.

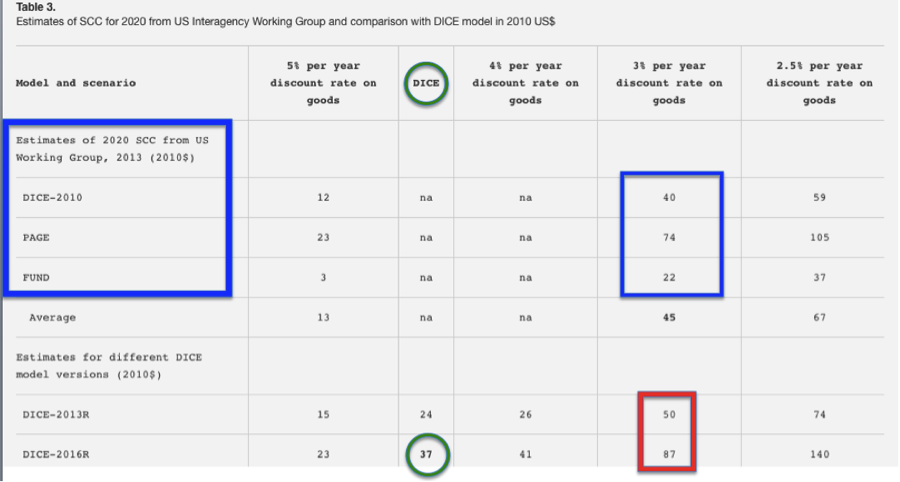

To give a flavor of how complicated this gets, consider the following table that I’ve reproduced from Nordhaus’ own 2017 article on the social cost of carbon, published in the (prestigious) Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS):

As the table shows (click to enlarge), as of the latest calibration of his model in 2016, Nordhaus thought the best estimate of the SCC for the year 2020, measured in 2010 dollars, was $37/ton of carbon dioxide. (I circled it in green.) This was actually $3 per ton less than what the Obama Administration Interagency Working Group had estimated for the SCC back in 2013, using the 2010 version of the DICE model. (In the table, I put blue rectangles around all of the Obama Working Group’s estimates—relying on DICE and two other models.)

So does that mean Nordhaus thought the threat of climate change had fallen from 2010 to 2016? No. As I show with the red rectangle, by 2013 Nordhaus’ model would have increased the $40 estimate to $50, and by 2016 it increased to $87—more than doubling in six years!

What the heck is going on here? The answer is that back in 2013, when the Obama Working Group used the 2010 version of DICE (as well as the then-up-to-date versions of the PAGE and FUND models), they plugged in a constant rate of discount on future goods. The generally accepted middle-of-the-road figure was 3%, and that’s why everybody said, “Nordhaus’ model says the SCC is $40/ton.”

Yet Nordhaus himself doesn’t think this is the economically correct way to proceed, and prefers to use market-derived tradeoffs between present and future goods. (Note that the discount rate on goods isn’t the same thing as the “pure rate of time preference” mentioned in Tol’s paper; click through and read Nordhaus’ PNAS article for a good but technical explanation.) In other words, back when the Obama Administration used Nordhaus’ model to estimate the SCC, they plugged in some assumptions that at the time vastly overstated the SCC, relative to how the model’s developer himself thought proper.

Besides showing just how complicated this all gets, and why the innocent outsider will have a tough time “checking the literature to see what the consensus SCC estimate is,” there are two takeaways from the table above:

- It wasn’t just Nordhaus’ DICE mode, but two others that were selected by the Obama Administration to calculate the SCC. For the 3% discount rate, Richard Tol’s FUND model spat out a $22/ton estimate, while Chris Hope’s PAGE model gave a bigger estimate of $74/ton. There was no cherry-picking in the selection of these models; in my years of reading this literature, I have not seen a single complaint that some other model was more representative of the state of the art than these three. So when Wagner writes “my co-authors, Kent Daniel and Bob Litterman, and I were unable to get the price below $100,” keep in mind that they were tying their hands in a very specific way. The scientists and wonks in the Obama EPA had no problem using the top-3 models from the literature to generate SCC estimates well below $100.

- Nordhaus has continually updated his model in light of developments in both economic theory and to make the underlying climate model fit the physical science literature better. It’s not at all the case that “climate economics” has moved on, leaving the veteran in the dust. Nordhaus himself has written responses to challenges coming from (among others) Wagner’s own mentor and hero, the recently (and tragically) deceased Martin Weitzman. Maybe Nordhaus is right or maybe he’s wrong, but this isn’t a case of Isaac Newton versus Albert Einstein, as Wagner’s article would lead the innocent reader to believe.

Wagner Only Considers Factors That Increase the SCC

The fundamental problem with Wagner’s glib discussion is that he brainstorms and throws out some considerations that all push the SCC up. But there are other considerations that push the baseline theoretical estimates of the SCC down.

For example: Although they don’t often spell it out (Nordhaus himself is a happy exception, for he does talk about it at length in his book A Question of Balance), when economists estimate the “optimal” carbon tax they are assuming it is implemented worldwide and stays in force for decades to come. For if China and India (say) don’t implement a carbon tax while only Europe, Canada, and the US do, then the “optimal” carbon tax in those regions ends up being lower because of “leakage,” where some emissions migrate from the taxed to the untaxed jurisdiction. The actual experience with carbon taxes around the world shows that they are often scaled back or eliminated entirely when the public grows tired of high energy prices.

Another huge problem is that the optimal carbon tax should take account of the pre-existing tax code. Contrary to intuitive (yet wrong) claims, the baseline result in the peer-reviewed literature on the so-called “tax interaction effect” is that distortionary income and capital taxes actually reduce the case for imposing even a revenue-neutral carbon tax. At an IER panel that I helped organize, economist Ross McKitrick—who is the author of a graduate-level text on environmental economics—made a plausible case that when you consider the tax interaction effect and some other factors, the “optimal” carbon tax is close to zero.

Finally, we can use good old-fashioned political economy: Regardless of the theoretically “optimal” carbon tax, what are the odds that we can trust the political process to actually implement it and keep it at that level over the coming decades, especially as the budget hole from entitlement programs and net interest gets deeper and deeper? The advocates of a carbon tax never even mention this, let alone do they plausibly account for it in their “modeling.” (All of these objections are discussed in my Cato article co-authored with climate scientists Pat Michaels and Paul Knappenberger and my own IER study.)

Conclusion

The global climate and the global economy are both incredibly complex systems, and it is ludicrous that so many academics are trying to anchor tax policy in projections of how carbon emissions today will affect the temperature in the year 2100. So if Gernot Wagner and others want to point out all of the shortcomings in the exiting literature, fair enough.

Yet Wagner wraps up his Bloomberg article by saying: “By now, climate economics…knows $40 to be woefully inadequate… A baby step is for economists to stop talking about $40 as if it were a sensible starting point. It is not. Try $100 or more instead.” The average reader would think that “the experts” all agreed with Wagner, and yet as I’ve shown above, this isn’t the case at all.

Some experts—such as Wagner’s (late) co-author Martin Weitzman—think the consensus in the literature is wrong, but Weitzman and Wagner don’t speak on behalf of “climate economics.” Wagner and Weitzman are actually deviating from the consensus. It is amazing that the same camp beating right-wingers over the head for “denying the consensus” on climate science then throw out (much of) the peer-reviewed literature when it comes to the economics of climate change.

______________________

[1] A note for purists: Tol’s accompanying chart in his tweet at first glance looks like it supports Wagner’s case (because the relatively constant median estimate of the SCC is high), but the problem is that Tol doesn’t specify his units or the assumptions behind the chart. (I asked him to clarify but as of this writing he hadn’t answered me.) In any event, see my discussion of Nordhaus’ table in the text above to understand why these considerations are so important.

The post Gernot Wagner Misleads on Social Cost of Carbon appeared first on IER.