A recent piece in The Week on the climate change debate is at once refreshing and disappointing. On the one hand, the author Jeff Spross tries to be fair to the opponents of government intervention into the energy sector. He agrees that they aren’t “science deniers” and goes so far as to concede that they know the science as well as the alarmists clamoring for stringent new regulations and taxes.

On the other hand, Spross is still a supporter of vigorous government intervention, and he uses the analogy of insurance to justify his stance. Yet Spross’s case is flawed. He misunderstands the IPCC report: the economic damage from popular climate change policies is projected to be 80 times higher than what Spross tells his readers. Furthermore, even on his own terms, Spross hasn’t really shown that the popular proposals to combat climate change make sense. Nobody—including Jeff Spross—would buy life or car insurance on these terms.

Spross Misstates the Economic Damage of Climate Change Policies

Although it was no doubt an honest mistake, Spross seriously misleads his readers on what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported in its most recent publication on the estimated costs and benefits of government policies designed to mitigate climate change. Here’s Spross:

Insurance comes in many forms: You pay premiums so health insurance companies will some day pay for your care. You buy homeowners insurance in case disaster strikes your house. And if you ride a motorcycle, you buy “insurance” by purchasing an expensive leather jacket and helmet that will protect you in case you ever crash.

Insuring against climate change is more like the latter example: We need to spend money on a whole lot of things now — constructing solar panels and windmills, research and development of batteries, smart grids, building weatherization, electric cars, etc. — to avoid losing a whole lot more money to storms and heat waves and water shortages and sea-level rise down the road. Pinning down exactly how much that would cost is horribly tricky, but the models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) generally put it at around 0.06 percent of global GDP per year.

But the key thing is that we make climate change less about science and more about risk management. Because once we all agree we’re discussing risk management, we can discuss the potential risks more concretely.

The IPCC’s models also project climate change could reduce global GDP by as much as 5 percent by 2100, assuming the world’s current-but-inadequate efforts to reduce carbon emissions stay on course. That’s obviously a lot more than 0.06 percent. But maybe, given all the uncertainties, 5 percent itself doesn’t seem like much to panic over. [Bold added.]

So at this point, Spross’s readers would think that the IPCC was projecting that if the governments of the world continue to twiddle their thumbs, then by the year 2100 climate change damages will have reduced global GDP by 5 percent compared to what it otherwise would have been. In contrast—so Spross’s readers would think—humanity could avert that hit to the globe by adopting policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn would only reduce global GDP by 0.06 percent.

If those were indeed the numbers, what kind of a fool wouldn’t jump at that bargain? Why wouldn’t we want to make global GDP 0.06 percent lower in 2100, rather than 5 percent lower?

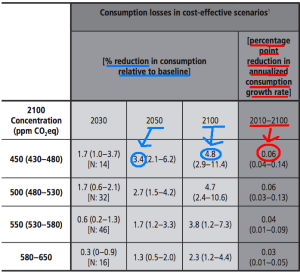

There are two huge problems here, one blatant and one more subtle. The first problem is that Spross (relying on this Grist article) misunderstood the “0.06 percent” figure. Below is a table taken from an early draft of the IPCC’s latest report:

IPCC’S TABLE SPM.2. Global Mitigation Costs From Emissions-Reductions Policies

Source: Early draft of IPCC Working Group III AR5 Summary for Policymakers, p. 16

I gave more context in a previous IER post, but for our purposes here, I’ve marked up the relevant elements of the table.

In order to “likely” limit total global warming to 2 degrees Celsius—which is considered the maximum acceptable ceiling by many activists, and which was adopted as the formal ceiling in the Paris Climate Agreement—the IPCC document specified that in the year 2100 atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases had to be limited to 450 parts per million of CO2-equivalent, meaning that we are looking at the top row of the table above.

In red, I’ve circled the 0.06 percent per year figure that Spross cited. However, that figure means that if governments adopt policies to limit atmospheric concentrations to 450ppm, then global economic growth will be 0.06 percent points slower every year during the period 2010 – 2100. For example, if normally the global economy would have grown on average 2.5 percent every year during this 90-year period, then with the emission reduction policies in place, instead, global consumption will only grow 2.50 – 0.06 = 2.44 percent every year in this period.

That doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it has has a huge cumulative effect. The middle columns, for example, show (in blue) that global consumption will be 3.4 percent lower in the year 2050 relative to the baseline and will be 4.8 percent lower in the year 2100.

Remember that Spross had suggested that, in the year 2100, unrestricted climate change damages would mean a hit to global GDP of about 5 percent, while the economic cost of avoiding it would only be 0.06 percent. We see the true cost (as projected by the IPCC) is actually 4.8 percent i.e. 80 times higher than what Spross thought. Now, instead of looking like a great bargain, using the IPCC’s own numbers,[1] we see that the “bare minimum” target contained in the Paris Agreement is closer to a wash.

Oh, wait—it gets worse. The net benefit of climate mitigation policies is the difference in climate change damage from “business as usual” versus “limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius.” In other words, it’s not correct to compare the economic impact of 4.8 percent with the climate damage of 5 percent, because even if the Paris Agreement target is achieved, most models predict some climate change damages even with 2 degrees of warming.[2] So the net benefits of the government policies are less than 5 percent, even though (as we’ve seen) their cost is still 4.8 percent, making the whole proposition even more dubious.

Would You Buy Insurance Like This?

However, even after correcting for the (enormous) mathematical misunderstanding, Spross might try to resurrect his basic point: “Sure,” he could argue, “humanity will probably ‘spend more’ in terms of forfeited economic output on government mitigation policies than we will ‘save’ in the sense of avoided climate change damage, but isn’t that true of insurance in general? After all, doesn’t the typical home owner ‘lose money’ on fire insurance, and doesn’t the typical motorist ‘lose money’ on car insurance?”

It is certainly true that people buy insurance in the private market because of “risk aversion” and not because it’s an actuarially profitable investment. For example, if there is a one-in-a-thousand chance that your $200,000 house will burn down each year, then the fire insurance company will charge you more than $200 in annual premiums, because they have overhead expenses and so need to charge more than the “breakeven” amount.

Even so, you as a homeowner would gladly pay (say) $300 to eliminate the actuarially expected loss of $200 on your home, because you’ve translated the uncertain outcome into a known (and small) loss. Because most homeowners are risk averse, it is possible to have win-win fire insurance contracts where large companies pool thousands of customers and issue blocks of policies, where they “make” $100 per policy per year on average in order to cover their expenses and earn a return on their invested capital.

So now we have to ask: Is this a good analogy for the climate change debate? And the answer is: absolutely not. As I wrote in a previous IER post that analyzed this topic more thoroughly, after running through some of the numbers from the IPCC reports:

Suppose someone from an insurance company came to you in the year 2050 and said, “We’ve run computer models many thousands of times using all kinds of different assumptions. In the worst-case scenario, a very small fraction of the computer runs—about 1 in 500—has you losing 20% of your income in the year 2100. In order to insure you against this extremely unlikely outcome that will occur in half a century, we want to charge you 3.4% of your income this year.”

Would you want to take that deal? Of course not. The premium is way too high in light of the very low probability and the relative modesty of the “catastrophe.” When someone’s house burns down, that’s a much bigger hit than 20% of annual income. And yet, the premiums for fire insurance are quite reasonable; they’re nowhere near 3.4% of income for most households. Moreover, the threat of your house burning down is immediate: It could happen tomorrow, not just fifty years from now. That’s why people have no problem buying fire insurance for their homes. Yet the situation and numbers aren’t anywhere close to analogous when it comes to climate change policies.

Other Problems With the Insurance Analogy

There are other ways of seeing the problems with this analogy. For example, Spross likens climate policies to wearing a helmet when you ride a motorcycle, or to “insuring” against colon cancer, but he doesn’t actually do the work to translate from the IPCC’s numbers to show that these analogies work.

Ask yourself: Why do people wear a helmet when they ride a motorcycle? It’s because, for the type of accident that is admittedly unlikely but nonetheless catastrophic, it would do a lot of good on the margin to be wearing a helmet.

In contrast, we don’t wear helmets when we fly in commercial airplanes. It’s not because we are certain there won’t be a crash, but because (in that unlikely but catastrophic scenario) having a helmet on is going to make a big difference. In contrast, it would be silly to bear the “cost” of wearing a helmet all the time when you fly.

Turning to cancer: Spross doesn’t say what “insurance” he has in mind, but presumably he means regular screening for people of a certain age. Again, we have to compare marginal costs and marginal benefits. Nobody recommends that eight-year-olds in Ghana get screened every month for colon cancer; that would be ridiculous. If the UN passed a measure insisting on such procedures, it would make everybody worse off.

Future Generations Will Be Much Richer Than We Are

It is not enough for Spross and others to merely invoke insurance as if that solves the matter. No, they need to show that the numbers actually make sense. As I argued above, you probably wouldn’t pay a big chunk of your income to only partially insure against a very unlikely (but much bigger) loss that wouldn’t occur for decades.

What people often overlook in the climate change policy debates is that the severe outcomes that occur in the computer simulations typically don’t kick in until many decades down the road. Even if governments “do nothing,” so long as they get out of the way and allow conventional economic development, the future generations dealing with climate change (and AI, and biological warfare, and killer asteroids, and all sorts of other problems we can’t even imagine) will be much richer than we are today.

For example, just throwing together some ballpark calculations (from here, here, and here), it’s a decent guess to say that in the year 2100, real global economic output will be more than seven times as high as it is today, while the world population might be a bit higher than 11 billion. So, if current estimates put real GDP per capita at around $17,000 per year, by the year 2100 each Earthling on average will enjoy a standard of living of more than $70,000 per year.

So let’s say disaster strikes and the global economy is cut in half by the year 2100 compared to what otherwise would have been the case without climate change. Even so, with our ballpark figures that still means per capita income will have more than doubled rather than quadrupling.

Conclusion

Although he tries to be fair to the opponents of government intervention in the name of fighting climate change, Jeff Spross still makes a very weak case for activism. In addition to seriously botching an important number, he doesn’t really provide the right type of argument to make the insurance analogy work.

Beyond that, Spross and others need to remember that we’re talking about future generations who will be much richer than we are. We’re talking about hobbling energy development today in order to make the Earth a few degrees cooler for people who will probably have robots fly them to work.

[1] Strictly speaking, the economic cost measures are often expressed (as here) in terms of “consumption,” not “GDP.”

[2] For example, in Table A-1 of this paper from William Nordhaus, we see that in his “optimal” run, by the year 2050 the globe still experiences 2.11 degrees of warming, and has suffered a 1.1% hit to global output by that point.

The post Switching to Markets Could Save You 15 Percent or More on Climate Insurance appeared first on IER.

No comments:

Post a Comment